Amazon’s Pricing Policies Promote Inflation

The state of California has sued Amazon in what may be the biggest antitrust case for 25 years, when 20 states joined the US Department of Justice to sue Microsoft. These cases revolve around whether consumers are harmed by the company’s actions. The case against Amazon focuses on their pricing policies. Here’s how they work and why they allegedly cause consumer harm.

Amazon prohibits sellers from pricing their products lower off-Amazon, than they do on-Amazon.

If we sell our educational building toy Brain Flakes for less on Walmart.com, than we do Amazon, Amazon will hide Brain Flakes on Amazon.

Amazon accounts for over 90% of our revenue, so we cannot afford to have our products hidden on Amazon.

For many of our products, it is much cheaper for us to sell those products off-Amazon than on-Amazon. As such, we could offer them off Amazon, for lower prices than on Amazon, and still make the same amount of money, but because of Amazon’s pricing policy, we are unable to this. In this way, Amazon’s pricing policies are causing inflation by preventing us from lowering prices where our costs are lower.

I first wrote about this problem in 2019. Since then, three things have happened. First, multiple government entities have either started investigations into Amazon’s pricing policies or have sued Amazon. Second, many have argued that I’m wrong, that Amazon’s policies don’t raise prices for consumers. Third, for the first time since the 1970s and 1980s, inflation has once again reared its ugly head in the America, making this question of pricing all the more important. In view of this question’s newfound importance, I decided to write an update to my original article, addressing criticisms and questions spurred by the original article.

Why can’t you just sell off-Amazon?

Amazon accounts for too large of a percentage of US toy sales for us to do that. In 2019, Amazon accounted for 98% of our sales. In the four years since, we’ve made reducing our reliance on Amazon a focus every year, but all we’ve been able to achieve is reducing Amazon’s share of our sales to 90%. In reality, that number is probably around 92% because much of our off-Amazon sales are made to distributors who resell our products on Amazon in the UK, EU, Japan, and Australia.

Don’t customer acquisition costs make Amazon vs. website cost comparisons apples to oranges?

The above Brain Flakes building set sells for $69.99 on both Amazon and our website. However, were it not for Amazon’s pricing policies, we could lower our price on BrainFlakes.com to $66 and make roughly the same profit we make on Amazon. But what about the cost of getting customers to our website? There are millions more people visiting Amazon.com every day than there are on BrainFlakes.com. It costs money to bring those people on Amazon to your website. By the time you pay Facebook and Google to do that, the cost of the $66 Brain Flakes set might be $80 or $90 to ensure the same profit on Amazon.

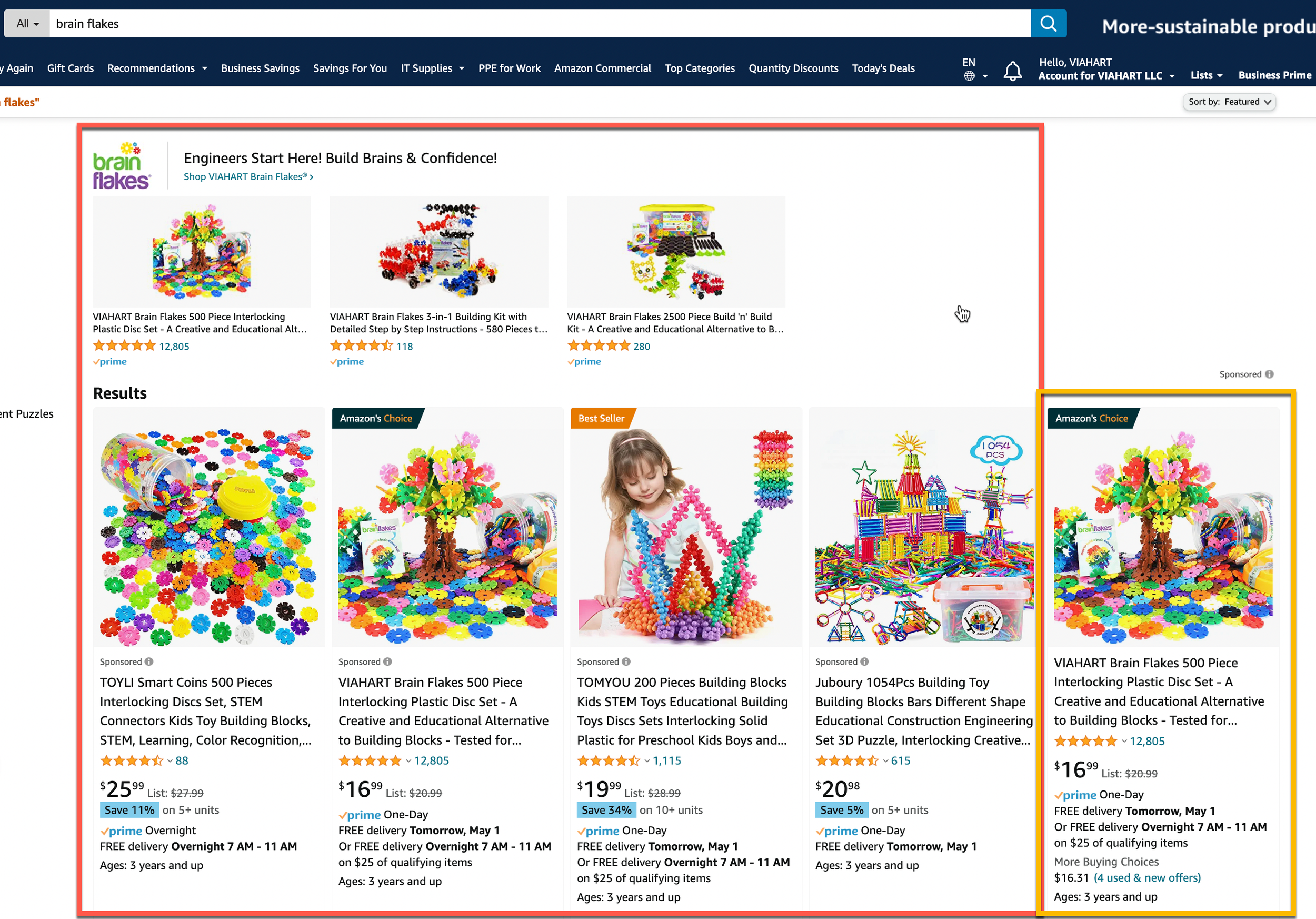

There are a couple of reasons why this line of thinking isn’t accurate. First, just because millions of people are visiting Amazon.com every day, doesn’t mean they’re seeing your products. We spent nearly $100,000 to advertise our products in Amazon searches in 2022. For example, in the below search for our brand Brain Flakes, everything in the red box is an advertisement that a seller is paying Amazon to show. Only the yellow box is an organic result.

Secondly, we don’t necessarily have to pay customer acquisition costs for our own website. If sellers could price their products lower on their own websites and word got out that they were doing this, price-sensitive customers could search Amazon and then check the seller’s or brand’s website to see if they could get a better deal there — no expensive Facebook or Instagram ad to the brand’s website required. Customers could choose between the cheaper, possibly slower-shipping website and the Amazon prime they know and love. Unfortunately, Amazon’s pricing policies restrict consumers from doing that by preventing sellers from pricing lower off-Amazon.

Further, sometimes the same-profit pricing discrepancy is much larger than $69.99 vs. $66. We’ve had products that sold for $150 on Amazon, which could be sold on our website for $113 at the same profit per unit. Under Amazon’s pricing policies, we are unable to spend $20 on Google and Facebook ads to drive customers to our website, where they would find the same product at $113 + $20 = $133, instead of $150 on Amazon!

Aren’t Amazon’s pricing policies are the same as minimum advertised pricing (MAP) agreements in old-school retail?

Here’s how MAP policies work. If you want to maintain a relationship with the Colgate, you must agree not to advertise their toothpaste for sale below Colgate’s designated MAP price. While you have the right to sell Colgate toothpaste for whatever price you like, Colgate has the right to not sell to you again if you go below their minimum advertised price. While this is illegal in Europe, it’s legal in the United States.

How is this different from Amazon’s pricing policies? For one, stores don’t need to sell Colgate, because they can sell Crest, Sensodyne, Aquafresh, Arm and Hammer or even their own store brand, but most brands do need to sell on Amazon because Amazon is so much bigger than Walmart and eBay, the next biggest online sales channels. Secondly, it’s not the brand that is setting the pricing, but instead the store, Amazon, which is different from MAP agreements. Third, Amazon does not allow sellers to divert their customers; telling Amazon customers that they could buy the brand’s product for less on the brand’s website, would likely result in suspension from Amazon.

Even if Amazon’s pricing policies raise prices for consumers, could they afford to charge less?

Amazon has managed to promote the narrative that their retail operations are money-losing operations. It doesn’t pass the smell test, and we know from looking at other marketplaces that they could probably charge less. Amazon is the dominant marketplace in almost every market it operates in, but let’s look at other countries'. In China, Alibaba’s Taobao doesn’t charge a commission on every sale like Amazon does and makes all its money on advertising and payment processing alone. Indonesia’s leading marketplace Tokopedia charges 1% to 4.5% in commissions on sales. Korea’s Coupang charges 4% to 10.8%. And it’s not just foreign companies, Etsy, which largely doesn’t sell products available on Amazon and thus bypasses the Amazon pricing policy, has transaction fees of 9.5%, lower than Amazon’s typical 15%.

Doesn’t Amazon just need a low-cost competitor to shake up the market and lower prices for consumers?

Because Amazon is many times bigger than Walmart.com, Walmart reducing its selling fees to 0 would not reduce prices on either Amazon nor Walmart. That’s counter-intuitive, but it follows from Amazon’s pricing policy. If Walmart were to lower its selling fees to 0 (Walmart’s fees mirror Amazon’s), sellers could sell their products for much lower right? It turns out they can’t, because in the process of doing so, their products on Amazon would become hidden and Amazon is the main source of most sellers’ sales. When Walmart lowered their free shipping minimum for consumers to $25, Amazon quickly matched, but if Walmart lowered its selling fees to 0, Walmart sellers wouldn’t lower their prices on Walmart, because they can’t without losing their bigger Amazon business. Walmart would just end up losing money with the newly lower fees.

Conclusion and hope for the future

I hope I’ve managed to explain clearly how Amazon’s pricing policies raise prices for consumers. I’d like to think that Amazon is not doing this deliberately, that a combination of hubris and ignorance has caused them to create and then enforce this wrongheaded policy. In 2022, the fees Amazon charged us to ship out our products went up an average of 45% making our website, Walmart, and eBay considerably more cost-competitive, but because of their policies we are unable to take advantage of this by lowering prices to drive volume to these more profitable sales channels. I hope Amazon changes their mind and gets rid of this dumb policy. I’d like to be able to set our prices online without worrying that we’re going to get our products suspended on Amazon. And, much more importantly, in this inflationary environment, American consumers deserve to pay less than they are online.